Exploring Cultural Legacy and Personal Identity

If Western experts or Chinese scholars fail to grasp Sun Yat-sen’s remark that “every Chinese person has an emperor in their heart,” they may not be fully qualified to discuss Chinese issues. Sun Yat-sen, a revolutionary and political figure from over a century ago, made this statement to highlight a deep-rooted belief that, throughout Chinese history, people either aspired to become emperors or were content to live as subjects under one—a mindset that endures to this day. Many of China’s current challenges stem from this “emperor complex.” Traditionally, Chinese society was one where peasants dreamed of rising to the status of emperor, or, if unable, longed for a wise ruler to lead them.

Consequently, the Chinese system was not structured with the emperor serving the country, but rather with the country existing for the emperor. The entire state apparatus was designed to serve the emperor and his family, with the political system organized to maximize their power and interests.

Throughout China’s more than 2,000-year history, there were 559 emperors, with lifespans ranging from 2 to 89 years. Many of these emperors were not born into nobility; some, especially key figures, were cunning peasants who led rebellions and rose to power. This set an example for future generations, suggesting that anyone could become emperor. While it wasn’t a reality for everyone, the idea of the emperor became deeply ingrained in the Chinese psyche, like a cultural gene embedded in their collective consciousness.

The Dream of the Emperor among Chinese farmers and their attempts to realize this dream can be seen as a phenomenon that is particularly notable within the Chinese context. In some remote and impoverished villages, uneducated peasants dare to declare themselves as emperors. Even after the Communist Party came to power in 1949, proclaiming the abolition of feudal superstition, there were still hundreds of cases of “wild” emperors in China. Of course, not all of these cases involved attempts to overthrow the government. Some simply indulged in the fantasy of being an emperor behind closed doors, with their subjects playing along as ministers, generals, or advisors.

Despite Mao Zedong’s claim of establishing a socialist China after 1949, his regime was essentially a traditional imperial state where the emperor had the final say. Mao, the foremost leader of the Communist Party, who had humble peasant origins, once admitted to seeing himself as an emperor. After Mao’s death in 1976, more than a hundred farmers in China’s rural areas believed themselves to be emperors over the next 17 years until 1993. These incidents occurred in various provinces of China as the farmers inherited a gene that made them see Mao as the most recent emperor and believed they had a chance to become one themselves. The popularity of being an emperor is evident from these occurrences.

These ambitious peasants not only held coronation ceremonies but also awarded themselves titles, selected consorts, and even formed armies in an attempt to overthrow the government. However, most of these emperor dramas were nipped in the bud by local Communist Party governments before they could develop into something significant. Nevertheless, at least ten of these wild emperors had a significant impact during their time. Their end was not becoming an emperor but receiving a life sentence or a death sentence. Here, only four famous examples are mentioned.

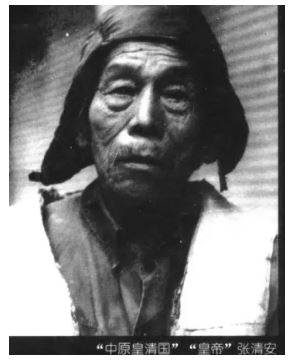

Zhang Qing’an(张清安), a farmer from Sichuan province, knew some medicine and fortune-telling and deceived some people. In 1982, he declared himself emperor and seized the building of a Sichuan opera troupe as his “palace,” preparing to confront the Communist Party army. This emperor prepared a pound of peas for each person and told his subjects that by scattering the peas, they could turn into celestial soldiers and generals.

Additionally, each warrior ready to resist was given two bundles of horse ear grass to tuck into their waistbands, which would transform into wings during battle. They were also given a bamboo tube, and by aiming it at the enemy and reciting a spell, they could unleash divine fire to destroy their foes. It can be imagined that this kingdom was quickly eliminated by the Communist Party’s army, and the emperor was captured and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Ding Xinglai(丁兴来), a peasant from Hubei province, who was blind, successfully fulfilled many people’s emperor dreams that they did not dare to pursue. Starting in 1981, he declared himself emperor and ascended to the throne.

Ding Xinglai ruled for ten years with great skill, and he had a special talent as an emperor. He helped female patients by giving them “divine energy” through sexual intercourse. He deceived the ignorant locals and took more than 60 concubines, including mother-daughter pairs, sisters-in-law, sisters, and mother-in-law and daughter-in-law pairs. He demanded that these concubines accompany him to bed and, as a reward, he appointed them as members of his loyal court and bestowed imperial titles upon them.

By 1990, he was banned by the Communist Party after successfully reigning for ten years, controlling eight nearby towns and having his own subjects. He created an incredible thing in Communist Party society.

Cao Jiayuan(曹家元), a farmer from Sichuan province, declared himself the “Jade Emperor” in 1982. Not only did he demand that the villagers offer up their most beautiful women to serve as his favorites, but he also personally led a group of dozens, akin to his royal guard, to storm the local government office. There, he confronted the party’s attractive female cadres, insisting that they become his loyal concubines.

These women, brainwashed by Communist ideology, were baffled as to how they could possibly accept that a mere farmer had suddenly proclaimed himself an emperor. In the midst of this farcical scene, it wasn’t long before the government dispatched the military, swiftly bringing his short-lived dynasty to an end.

There was a farmer named Zeng Yinglong(曾应龙) who lived in Guang’an County, Sichuan Province, in 1985. By the way, this county, which is also the hometown of the second-generation leader of the Chinese Communist Party, Deng Xiaoping, can be expected to feel an even greater sense of pride, as it produced Emperor Deng Xiaoping. Zeng Yinglong fled to Xinxiang City, Henan Province, to avoid the one-child policy implemented by the local government. A group of farmers from Guang’an County, who were infuriated by the policy, planned a rebellion in the area. They believed that Zeng Yinglong’s name, which contained the character(龙) for “dragon,” and his current location in Xinxiang, which meant “new hometown,” signified that he would create a new country like a dragon. The farmers went to retrieve Zeng and made him their emperor. They dressed him in a dragon robe made by rural women and performed a coronation ceremony known as “yingjia” (迎驾), which means “to receive the imperial presence, ” when he returned to Guang’an County.

After Zeng Yinglong was crowned emperor, he immediately abolished the Communist Party’s one-child policy and encouraged women who gave birth to more than 10 children to be appointed as “noble women.” Leading thousands of followers, Zeng took over the county hospital, expelled the director, and captured the young female nurses, who were all made into his imperial concubines. When the local government sent troops to suppress his rebellion, Zeng forced the concubines, or nurses, to collectively commit suicide by drowning in a gesture known as “sacrificing for the country” to support his new dynasty. However, two of the nurses refused, and Zeng Yinglong’s henchmen killed them with a large knife.

After China entered the market economy in the 1990s, people’s focus shifted from aspiring to be emperors to making money. In 21st-century China, with surveillance cameras everywhere and big data monitoring everyone, it’s unlikely that farmers could organize and declare themselves emperors as they once did. However, the fascination with emperors endures, as seen in the many TV dramas featuring them. The desire for the entertainment, lifestyle, and the psychological impact of the emperor complex will persist for a long time.

At its core, the emperor complex is about the pursuit of unlimited power. Power dominates everything, and many seek it. Despite modern lifestyles with iPhones and cars, the psychological influence of the emperor remains strong. In today’s Chinese society, this structure is evident: in every organization, there’s someone wielding unchecked authority. In a city, the Party Secretary is the emperor; in a department, it’s the supervisor; in a company, it’s the boss; in a classroom, it’s the teacher; in a family, it’s often the father or husband. This hierarchical dynamic makes Chinese society, in essence, an “emperor’s society.”

In every organization, individuals pursue unchecked power, seeking control rather than fostering mutual respect and adherence to the law. This relentless drive to dominate leads to tragedy, as it perpetuates a cycle of oppression. Consequently, the emperor residing in the psyche of every Chinese person may take generations to fade away.